Mallards are hard to beat for grace and beauty. The drake’s dark-blue head shines iridescent green in the light, hence the nickname “greenhead.” All photos by author

“Dad, can I go with you?” I pleaded. “There’s no school tomorrow.” I enjoyed riding on patrol, weekends and sometimes after school—whenever I didn’t have baseball or basketball practice. Soon after moving to Northern California, I’d been given a copy of Francis Kortright’s classic, The Ducks, Geese and Swans of North America, and had become fascinated with waterfowl—so much so that at age fourteen I could identify just about every duck and goose in the Pacific Flyway.

—From The Game Warden’s Son

Cinnamon teal, mallards, and gadwalls at the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge. There’s no mistaking the gorgeous cinnamon-red plumage of the drake cinnamon teal. You have to be another teal to tell the difference between a hen cinnamon teal and a hen blue-winged teal, however.

“Greenheads and Muddy Sneakers,” one of the chapters in my sequel, The Game Warden’s Son, touches on a sad time in America’s history when market hunters decimated America’s waterfowl populations. Much of the damage was done in California’s wetlands, to feed multitudes of miners and fortune seekers passing through San Francisco and Sacramento during the gold rush. Most of this despicable activity ended with passage of the federal Lacey Act in 1900 and the hiring of state and federal wildlife officers to enforce newly established game laws. Some market hunting continued into the 1960s and beyond—much of it occurring in the waterfowl-rich rice fields of Glenn and Colusa Counties.

Northern shovelers at the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge. The so-called spoony is probably the most distinctive of all North American ducks. That spatula-like bill is a dead giveaway.

Warden Wally Callan transferred from marine patrol in Los Angeles to Glenn County in 1960. Our home was the tiny farming community of Orland, at the north end of California’s Central Valley. For the next ten years, my father was known to the citizens of Glenn County as “the game warden.” As the game warden’s son, I would experience outdoor adventures other boys my age could only dream of.

Gadwall drakes lack the bright colors of other male ducks but can always be identified by their yellow feet and white speculums.

It wasn’t long after we arrived in our new home that I engaged in a ritual most boys growing up in Orland considered a rite of passage. With instruction from the likes of “Trigger-Happy Harry”—one of the stars in a hunter education film—I learned the dos and don’ts of gun safety, passed the hunter safety exam, and bought my first hunting license. Next came my first shotgun—a secondhand, single-shot twenty gauge—unceremoniously handed to me on my twelfth birthday. “Remember what you learned in the hunter safety course,” my father said, “and don’t do anything to embarrass me.”

I’ll never forget that night in late November 1962 when I learned about market hunters—duck draggers as my father called them—for the first time. I invite you to experience that hair-raising event with me as I share this excerpt from “Greenheads and Muddy Sneakers,” the fifth chapter in The Game Warden’s Son:

Quietly locking both doors, I walked out to the paved county road and headed west. With a half-moon that night, there was just enough natural light to make the one-mile hike back to the old barn without using my flashlight and possibly alerting the duck poachers.

All I heard for the first half mile or so were flocks of geese chattering in the distance. Every so often, a drake mallard would pass overhead, wings whistling and quietly communicating his presence with a guttural kwek— kwek—kwek—kwek.

As I shuffled up the road, still agonizing over my decision to abandon Mercer’s car, my thoughts were suddenly interrupted by the faint din of human voices. What’s that? I asked myself. Did I hear someone talking? I stopped and listened. Nothing. I took a few more steps. There it is again. Standing perfectly still, I listened for the sound emanating from the rice field at the north side of the road. The voices stopped, but now I could clearly hear footsteps: someone was sloshing through the mud in my direction. I hunched down behind a patch of tules. The footsteps grew louder and I heard voices again.

They’re headed right toward me! I dropped to the prone position and quietly crawled inside the tule patch.Two men, not more than twenty feet away, reached the county road. Any closer and they could have stepped on me. Just like my father had said, they were wearing sneakers; I could tell by the squeaking sound their wet tennis shoes made as the men traversed the hard pavement.

From my hidden vantage point, I was able to see the shotguns the men were carrying and what appeared to be gunny sacks slung over their shoulders. As quickly as they had come, the suspected duck poachers reached the opposite side of the road and dropped out of sight. . . .

I don’t hunt anymore, but my insatiable interest in waterfowl hasn’t waned in fifty-five years. These days my wife, Kathy, and I pursue ducks and geese with a camera, relishing every second we spend sharing the wetlands with the wonderful birds that have inspired me for so long.

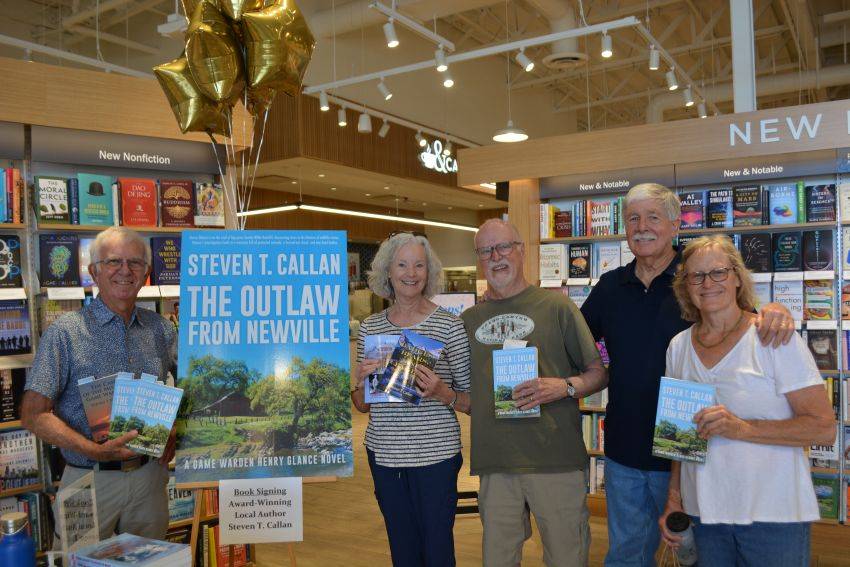

THE GAME WARDEN’S SON, my sequel to Badges, Bears, and Eagles, is available through online retailers, bookstores, and libraries.

This piece originally appeared as my January 12, 2016 “On Patrol” column in MyOutdoorBuddy.com.

6 Comments

Steve, this is a wonderful excerpt from your new book. I cannot wait to read it in its entirety.

Thank you so much, Annie.

Great teaser! Thats the area I would want to work if I was a Warden; coming down on those that take advantage of so many wintering waterfowl. Can’t wait for the new book!!

Thanks, Tony. The Sacramento Valley was a great place to grow up. There were ducks and geese everywhere in those days.

Really looking forward to having that book in my hands. Thanks for bringing memories back to life.

Thanks, Pete. You’re a good friend!