“Quick, roll up the windows!” said Kathy. We had just entered the ten-mile auto tour route at Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, when four cars roared by us like we were standing still. Pulling to the side of the road, we waited for the dust cloud that enveloped us to subside.

“Where did all these inconsiderate people come from?” I said, in slightly less delicate terms.

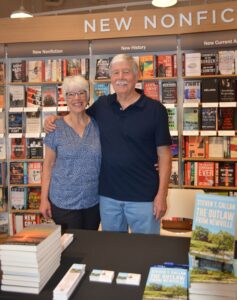

My wife and I love seeing and photographing wildlife, but our primary reason for coming to wildlife refuges, like Lower Klamath and Tule Lake, is for the serenity and enjoyment of experiencing nature. Competing for the next “photo op” was not what we had in mind.

I thought about a recent piece I had read in Ducks Unlimited magazine, entitled “Public Land Ethics.” The article provided ten rules for hunters to follow when hunting on public lands. Having enforced fish and wildlife regulations for thirty years, I was well aware of these rules—none of which were subject to enforcement—all of which require respect.

So, where am I headed with this train of thought? Respect is required of everyone who passes through a state or federal wildlife area—that includes photographers, bird-watchers and sightseers, as well as hunters. Visitors should respect the lands, respect the wildlife, and respect other visitors by showing them common courtesy. If you’re kicking up dust, no matter how dry the conditions, you’re driving way too fast.

After watching the dust clouds finally disappear, we slowly proceeded toward a stand of mature cottonwood trees at the west end of the auto tour route; according to one of the volunteers at the refuge visitor center, about thirty bald eagles had been frequenting the grove. Arriving at a flooded wetland, we began photographing an assortment of common duck species: mallards, pintails, gadwalls, widgeons, and buffleheads, along with massive concentrations of snow geese and white-fronted geese.

“Look, there’s a mature bald eagle up ahead,” I said. “Let’s see if we can get close enough for a photograph.”

“I’ll get the camera ready,” Kathy replied.

The majestic, white-headed bird sat motionless on the tip of a partially submerged snag while I inched the car within range of our 300 millimeter lens—close enough for a reasonably good photograph, yet not so close as to disturb the eagle. Kathy had depressed the camera shutter once or twice, when a sedan came roaring up behind us—its headlights on and a thirty-foot dust cloud in its wake. Hitting the brakes, the driver swerved to the right and came to a stop ten feet from our rear bumper. “There goes the eagle,” said Kathy. Thoroughly disappointed, we watched as the magnificent raptor disappeared into the marsh. As a general rule, wildlife will tolerate just so much human interference before vacating an area. By exhibiting no respect for us or the eagle, the driver of that car had pretty much ruined our experience.

Before leaving the refuge, we came to the much-talked-about grove of giant cottonwoods. All of the eagles had left, with the exception of one nesting bird. Parked beneath the nest were four cars, all unoccupied—it seemed everyone was spread out along the road, setting up tripods and operating camera equipment. A mustard-yellow SUV—its doors left wide open and blocking the road—was the cherry on the sundae. We stopped and waited while the driver walked back from his tripod and closed his door so we could pass. I had read in the refuge brochure that “staying in your vehicle will increase your observation opportunities.” Apparently, these camera buffs hadn’t read the pamphlet.

Leaving the refuge, I suggested that we get a good night’s sleep in Klamath Falls, wake up early, and check out Butte Valley Wildlife Area the next morning. Located five miles west of Macdoel, California, Butte Valley Wildlife Area contains 13,392 acres of wetlands, grasslands, and farmlands managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

It was a brisk nineteen degrees early the next morning as we left Highway 97 and headed up Meiss Lake Road toward the wildlife area. We had driven a mile or so, when we noticed an immature bald eagle perched on a power line at the side of the road. “This is already better than yesterday,” I said.

Arriving at the wildlife area, we spotted a sign reading Auto Tour Road. Driving out through this vast array of grasslands, wetlands, and open space, Kathy and I couldn’t help noticing that we were quite alone. “This is more like it!” I said. “We have the entire wildlife area all to ourselves.” To the south was snow-covered Mount Shasta, in all its glory. To the east were unspoiled grasslands as far as the eye could see. To the north and west were birds of every shape, size, and color. We identified twelve bald eagles, two golden eagles, and three rough-legged hawks within the first half mile. Immense flocks of snow geese lifted from the wetlands and landed again. Smaller flocks of swans punctuated the landscape, intermixed with a dozen species of ducks. As if that were not enough, sandhill cranes entertained us with their courtship ritual—jumping in the air, bobbing their heads, and flapping their wings—much to our delight.

Butte Valley Wildlife Area provided one of the most enjoyable wildlife adventures Kathy and I had ever experienced. I encourage others to share and enjoy this special place, with one very important condition: please show respect for the land, the wildlife, and other visitors. Above all, pass through quietly.

All photos by Steven and Kathy Callan

This piece originally appeared in my March 5, 2015 “On Patrol” column in MyOutdoorBuddy.com. It has been modified for posting on this blog.