“I’m waiting,” taunted Darrell, his threatening mug now two inches from my face. My stomach churned and my heart pounded furiously as adrenaline coursed through my body. I had painted myself into a corner. The question crossed my mind: Was I willing to get beaten up trying to protect a lizard? While Darrell and Randy laughed at me, I remembered something my father had said. Never start a fight, but the best way to end one is to hit the other kid in the nose as hard as you can. . . .

—From The Game Warden’s Son

Long before I knew what a Fish and Game warden was, I was fiercely protective of wildlife. In “San Diego,” the first chapter of my soon-to-be-released sequel, The Game Warden’s Son, I wrote about my early childhood living on the edge of a canyon in San Diego, California. At the age of nine, I defended a hapless alligator lizard from two neighborhood bullies. As I wrote in the book, “That was probably the first time I had engaged in the act of protecting wildlife, and it wouldn’t be the last.”

Twenty-two years later, as a patrol lieutenant for the California Department of Fish and Game, I would organize and initiate investigations throughout Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Riverside, and San Diego Counties, leading to a ban on the sale of native reptiles in California. During the 1970s, collectors were decimating native reptile populations in their attempts to supply the pet trade. Larger and more interesting reptile species, such as chuckwallas, desert iguanas, horned lizards, leopard lizards, collared lizards, and rosy boas, were in big demand, and some unscrupulous collectors would stop at nothing to cash in on this opportunity. I still remember filing charges against two Lancaster, California collectors who were in unlawful possession of several hundred horned lizards, desert iguanas, and leopard lizards.

So what’s the big deal? They’re just snakes and lizards, some might say.

Reptiles fill an important niche in the ecosystem. Most feed on insects, grubs, and spiders; some feed exclusively on slugs; and many feed on mice, rats, gophers, and ground squirrels.

Reptiles fascinate us, captivate us, and never fail to stimulate our curiosity. Some are brilliantly colored and decorated with intricate designs. Others are cleverly camouflaged to blend with rocks, sand, vegetation, and tree bark—try spotting a whiptail lizard under a shrub in dappled sunlight. Take a walk in the desert and you might find a reptile basking in the sun, slithering across the trail, darting across the landscape faster than the human eye can follow, or trudging through the sand at a tortoise’s pace.

Unlike birds and mammals, reptiles tend to be out of sight and out of mind. Banning the sale of native reptiles was a step in the right direction, but as California’s human population continues to grow, more lands, canyons, hillsides, wetlands, and open space will be buried under asphalt, houses, and shopping centers, eliminating critical reptile habitat. That’s why it’s so important to set aside and protect vast areas of undisturbed land, like Joshua Tree National Park and Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, where wildlife can thrive, and where present and future generations can enjoy our reptile friends like I did many years ago.

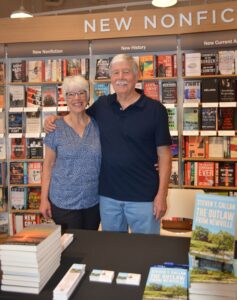

THE GAME WARDEN’S SON, my sequel to Badges, Bears, and Eagles, is currently available for pre-order on Amazon. It is scheduled for release March 1, 2016.

This piece originally appeared as my December 6, 2015 “On Patrol” column in MyOutdoorBuddy.com. It has been modified for posting on this blog.

2 thoughts on “Our Friends the Reptiles”

What a great article Steve. I have a lifetime of memories of reptiles and they are all good ones. You stirred up so many of them as I read this, so thanks. Cannot wait to read the new book.

Thank you for your kind words, Annie.

All my best,

Steve

Comments are closed.