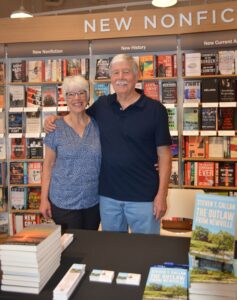

Out of Ventura Harbor we sailed this past November, in pursuit of a long-held dream. My wife Kathy and I had been waiting for years to visit Santa Cruz Island, the largest of California’s Channel Islands and part of the five-island Channel Islands National Park. We spent the day hiking the island and learning about the indigenous plants and animals that inhabit this fascinating archipelago, just twenty miles from the mainland. Being scuba divers, we were especially impressed by the crystal clear waters that surrounded the island, beckoning us to return someday with our scuba gear and underwater camera.

As the sun dropped lower on the western horizon, we headed back across the Santa Barbara Channel toward the mainland. About halfway across, we couldn’t help but notice a huge congregation of seabirds off in the distance. The boat captain must have noticed the commotion, because he slowed the boat to a few knots and steered us in that direction. As we approached, Kathy and I couldn’t believe our eyes: Hundreds of pelicans, shearwaters, gulls, cormorants, and petrels were diving into the water and circling overhead. The noise was deafening. Beneath the birds, hundreds, possibly thousands, of sea lions and common dolphins were porpoising in and out of the water, all in pursuit of the massive school of anchovies that swam beneath the surface.

It was a feeding frenzy, the likes of which most of us had never seen. People pushed and shoved their way to the bow of the boat. Cameras were cocked and ready, in anticipation of the ultimate outdoor experience—the granddaddy of them all—the wildlife sighting of a lifetime. As we anxiously waited, the birds suddenly quieted and the churning waters began to settle.

“What’s happening?” asked the passenger standing next to me, in broken English. “Why is it so quiet?”

“Just wait,” I whispered. “You’ll see.”

All eyes were on the birds, who directed their attention to a placid patch of silky smooth water lying a hundred yards off our starboard bow. Dolphins and sea lions raced toward the same location, some of them passing directly under the boat. About thirty seconds went by, when someone shouted, “There!”

Like a page out of Moby Dick, up from the depths came the cavernous maw of a humpback whale, followed by another and still another. Everyone on board stood spellbound, in absolute awe of these massive, forty-ton behemoths as they gorged themselves on the abundant baitfish.

I had seen great whales before, but for Kathy and me this was a deeply moving, almost religious experience. Here we were, eye-to-eye with one of the earth’s most magnificent and intelligent creatures. It felt good knowing that these gentle giants enjoy protection in U.S. waters under the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act. But how safe are they?

Whales in U.S. waters still suffer serious harm from unintentional sources: deadly encounters with commercial nets and fishing gear; sonar blasts from our own navy; collisions with boats and ships; depletion of fish stocks, as a result of excessive commercial fishing; point source pollution; nonpoint source pollution (runoff from multiple sources); and ocean acidification, caused by the continued burning of fossil fuels.

Dealing with these correctable issues here in the U.S. won’t end the cruel and inhumane practice of whaling by countries like Japan, Norway, and Iceland, but it will go a long way towards saving the whales and improving the health of our oceans. I would like to think that fifty or a hundred years from now, people will still be able to cross the channel to Santa Cruz Island and enjoy the same spectacular experience we had.

Photo by Cyndi Marlowe

This piece originally appeared in my January 27, 2014 “On Patrol” column at MyOutdoorBuddy.com.